|

|

|

|

© Dr. Artur Knoth |

Brazilian Philately: The Pan Am Zeppelin Flight of 1930 |

Aerophilatelic History: That Little Bit Extra – A 1930 Time Capsule (*)

Aerophilatelic as well as Postal History in general tends to naturally concentrate on the postal aspects and thereby miss the holistic context in relation to the role it played in that epoch's everyday life. Mr. Fricke's recent article was the impetus for finally putting to paper this larger, often neglected, aspect. The 1920's and 30's was an age of “Aufbruchstimmung”, a pioneer spirit, pulling up the tent poles to travel to new horizons, a technological “Manifest Destiny”. Ever larger buildings, new means of travel and communication, and a burst of economic globalization in the middle of the depression are found here. The first flight of the Zeppelin to Latin America, the May, 1930 Pan Am flight, and the mail it carried out of Brazil, represent a moment snapshot, a time capsule of the urban, personal and even economic history of that age. The picture postcards (PPC) and letters sent on this flight offer an intriguing glimpse of this 1930 epoch. These covers were franked with Brazilian stamps for the normal terrestrial rate and by private Luftschiffbau Zeppelin (LZ) company stamps printed in Germany. The basic set consisted of a 5$000-green (see Fig. 1a), 10$000-red and 20$000-blue, corresponding to the US-Zeppelins of 65¢, $1.30 and $2.65.

The Urban Aspect

Brazil: The picture postcards carried on this flight offer very interesting glimpses of not only Brazil but also of the US. Let's start with Brazil and the city of São Paulo. It's entertaining to see that today's megalopolis, once started more modestly. In Figure 1a and 1b, a local São Paulo dealer used the local postcards to create covers for a fellow foreign dealer. The private 5$000 Zeppelin stamp was for the postcard rate, the Brazilian postage is covered by the 300 Reis stamp. The picture is of the Martinelli building, and just as was the case for the Woolworth building in Fricke's article, here the claim is made of being the tallest building in all of South America. It is hard to imagine today's São Paulo started out with skyscrapers that modest then.

|

|

|

The situation portrayed by cards sent out of Rio de Janeiro are even more fascinating and an eyeopener. Just three dramatic examples of 70 years change. Everyone has seen pictures and heard of Copacabana and Ipanema beaches, with their broad beaches lined by a solid wall of tall buildings. Consider the Figures 2 and 3, and ponder the unbelievable scenes.

|

|

|

Both beaches are small and barely a tall building to be seen. In fact there are even completely empty lots and others with gardens or animal pens. In Fig. 2, at the far right, one sees the famous Copacabana Palace Hotel, standing all alone, even the hill next to it is gone. At most, two story houses are the rule. The beaches of today are a result of a landfill and sand dredging effect, that greatly enlarged them, decades ago.

The next Rio example is also impressive. Everyone recognizes the Christ Statue on the summit of Corcovado (710 meters high), much as the stamps in Fig. 4. But in 1930, that recently newly elected World Marvel, was still being assembled and was first dedicated on the 12th of October, 1931. Fig. 5 shows a card with an empty peak, and Fig. 6 documents the scaffolding erected for the construction of the Christ statue.

The last Rio example is one of things lost. At the end of the Avenida Rio Branco, the main street of downtown Rio, one found a small building known as the Monroe Palace. On two stamps out of a tourism series of the 1930's this building is displayed as a motive (Fig.7). The next two, Figures 8 and 9, are PPCs of that building along with a view of the Avenida too. This tree lined street with trees in the middle, dividing the two way traffic also no longer exists as such. Today it is a one way, multi-lane road out of hell, where between the taxis, trucks, buses and cars, a pedestrian never knows if he'll manage to reach the other side alive.

Years ago, Rio began an ambitious underground mass transport project, the Metrô. One of the downtown stations was Cinelândia, the park-like area in the foreground of PPC in Fig. 9. During the construction of the tubes and stations, the Monroe Palace developed such widespread and serious cracks, that the Palace had to be razed and Rio lost forever one of its more picturesque buildings. Needless to say, a tourist that visits Rio de Janeiro today, will, outside of the topography, not be able to even imagine what the Rio of May 1930 looked like.

United States: Just as the Brazilian dealers turned to their local PPCs for fashioning their covers, American dealers and aerophilatelists did much the same for theirs. Since the New York City region was one of the main philatelically active, one expects that a lot of NYC PPCs saw use. But Winfield, Long Island or Gardena, California are not cities that immediately come to mind.

Let's start with New York City PPCs. On this particular Zeppelin flight, one sees a lot of covers by Kullman and Sigel using these PPCs. Figs 10-14 display only a small selection of the PPCs encountered, as especially Sigel was very prolific in creating covers like these. At 65¢ a pop just for the 5$000 Zeppelin stamp for a single cover, not to mention the other postage and the card itself, Mr. Sigel, judging by the number one sees, had quite a lot of money on the table. Interestingly, one doesn't see either the Chrysler nor the Empire State Building since; at the moment of this flight, both were under construction and completed end of 1930 or 1931.

But the story of the covers confectioned by Gene Sigel has a special little twist to it. Consider Figures 15 and 16 which display the front of two Sigel cards.

The card with the handwritten address and the German air mail label (Fig,15) is always a NYC PPC. The other version, with the printed address and sent through the von Meister Zeppelin Agency (the 5 digit number) used PPCs with scenes of Winfield, Long Island. Seeing as Sigel lived in Long Island City, this last case isn't all that surprising. Looking at the Figures 17-20, we get a quick look at the highlights of Winfield at the end of the 1920's.

But without a doubt, the most fascinating case I've encountered is the Robertson cards out of Gardena, California. The Figures 21 through 24 displays the typical address side of the card, as well as three examples of Gardena scenes.

These cards are found franked with a 5$000 overprinted Graf Zeppelin – USA or as shown in Fig.21 with a 10$000 normal Zeppelin stamp (10$000 was the letter rate to the US, i. e. overfranked). Historically interesting could be the fact that at the time of the flight, Gardena, a suburb of Los Angeles wasn't even incorporated yet. That occurred several months later on Sept. 11, 1930.

Personal Stories

Up to now we've seen PPCs being used to create covers for aerophilatelists, who in no small way contributed to the finances of the LZ company and made the many flights even possible. But the Zeppelin, at least in the early phase, represented itself also as a way of getting greetings or messages to Europe faster than the few airmail possibilities and in any case weeks quicker than by ship. Here the Zeppelin offered a real tangible, albeit, expensive service for quick postal communications. Couple this to the fact that there were many families and businesses that had members who had emigrated or were stationed in South America, far from Europe and one sees that a clear demand for such services existed, even though expensive and not affordable for everyman in Brazil.

The first example, Fig. 25a and 25b, is a specially created PPC just like the example that follows. A private photograph was developed on the backside of the card. In this case, “Uncle Fritz” sends his greetings to relatives in the Ruhr region (Mülheim) of Germany.

The other example, again a private PPC, was sent from Bahia (probably the city Salvador da Bahia) to Denmark (Fig.26a and 26b), yet the text is written in German; perhaps a member of the German speaking minority. The photograph consists of a group picture of all their servants that take care of the house and grounds. This could be interpreted as a sign of how well the senders were doing in Bahia. Even today, but especially then, menial labor was very cheap, Europeans and Americans could enjoy such luxuries as the group of servants displayed on the PPC, that they would never have been able to afford at home. Since Bahia is north of Rio, an area which had a heavy slave population in Imperial times, most such menial labor consisted mainly of blacks. The postage on the card is an example of local improvisation on hand of the Condor company. The regular 5$000 Zeppelin stamps were relatively quickly used up. Since a lot of the more expensive 20$000 were left, a local printer overprinted a number of them for the 5$000 rate. Such a provisional was used to frank this card.

Economics and Finance

This section has three examples of how, already in the 1930s and in the middle of the Great Depression, the world's economies were already globally linked, globalization light if you wish. The very first example, Fig 27a and 27b, may seem trivial, but PR (public relations) is a very important aspect of doing business. Remember that may cigars are manufactured using either Brazilian or Sumatran leaf.

What better way to make an impression on customers and associates, then to use the Zeppelin's flight. A picture PPC of the Brazilian subsidiary of Suerdieck was sent on this flight. The Suerdieck Co., out of Westphalia, Germany has been in Brazil since the 19th century.

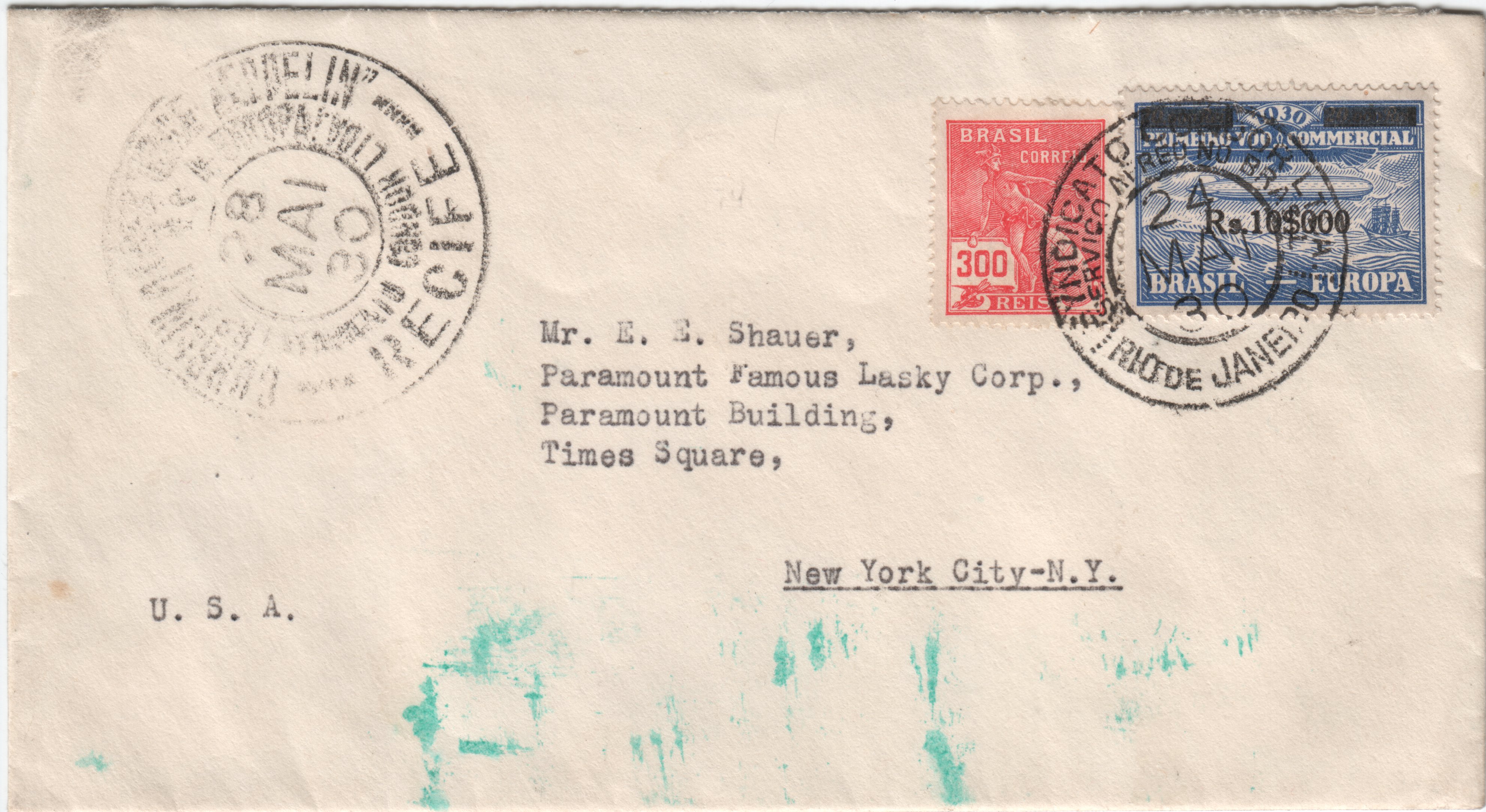

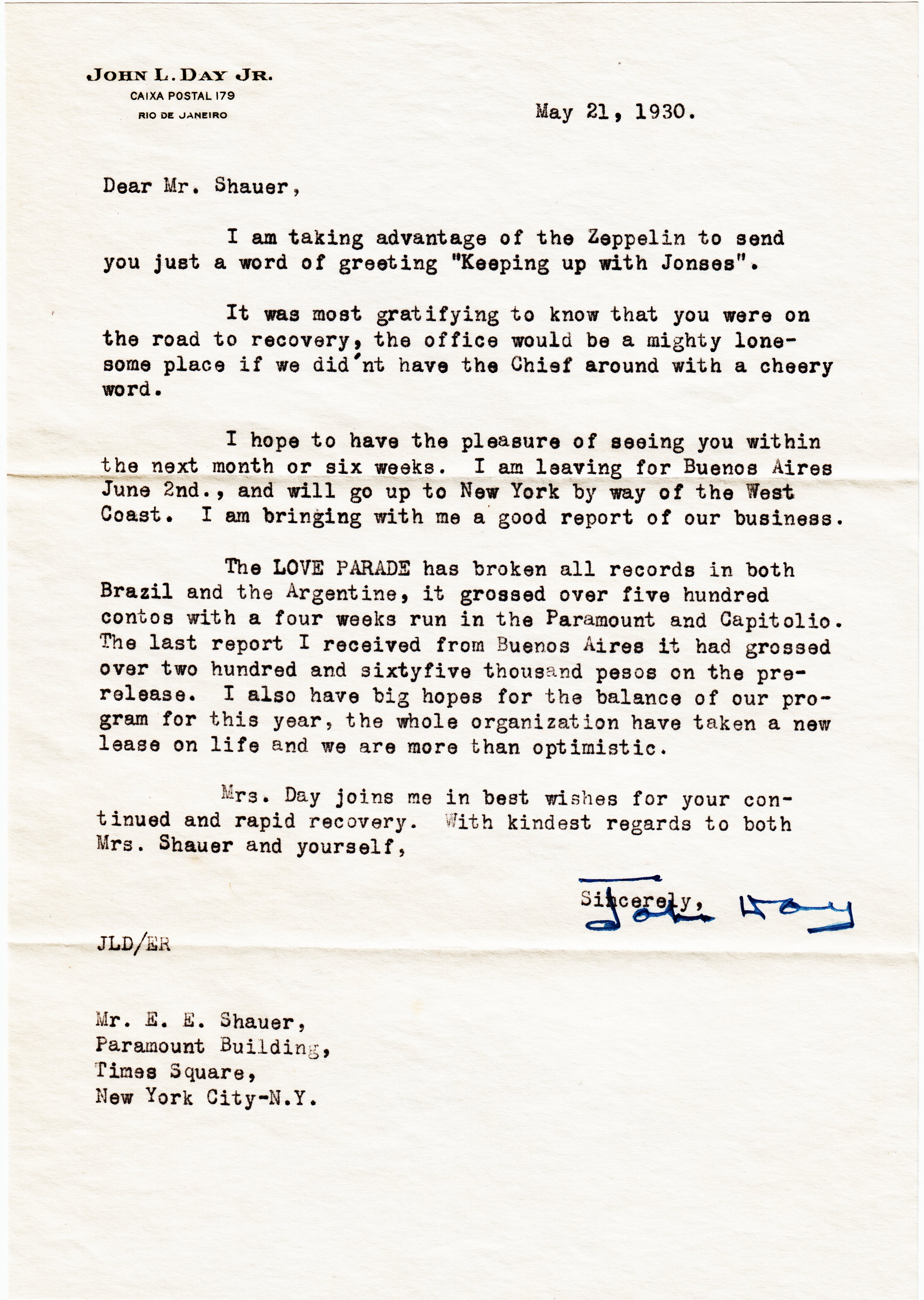

The next example is a case of extremely good fortune. When the cover shown in Fig 28a was purchased, I discovered that its still contained the original letter and was anything but a philatelic cover. The letter, Fig 28b, has a social message concerning the writer's supervisor, but also an economic one, giving the latest revenue results for the Paramount film “Love Parade” running in South America at that moment.

Fig. 28a: A very spartan, obviously unphilatelic cover sent to the

Paramount Co.

Fig. 28a: A very spartan, obviously unphilatelic cover sent to the

Paramount Co.

Fig. 28b: Letter with a financial results report.

Fig. 28b: Letter with a financial results report.

Here one sees that using the Zeppelin flight was a quick method of sending the latest financial results to the head office in New York. Just as an example, the Brazilian 500 Contos referred to in the letter are 500$000$000 in terms of Reis. If you now consider that 5$000 was on this flight about 65¢, then 500 Contos are roughly $65,000, which was a lot of money in 1930! This correspondence no doubt would of interest to topical collectors of film industry history. As a small detail of interest in this case, consider the picture in Fig. 9; on the right side of the plaza, the row of buildings you barely see, most had movie houses on the ground floor. More film theaters existed around the corner. Thus this part of Rio de Janeiro has long been known as “Cinelândia”, gave its name to the Metrô station underneath that caused the Monroe's demise.

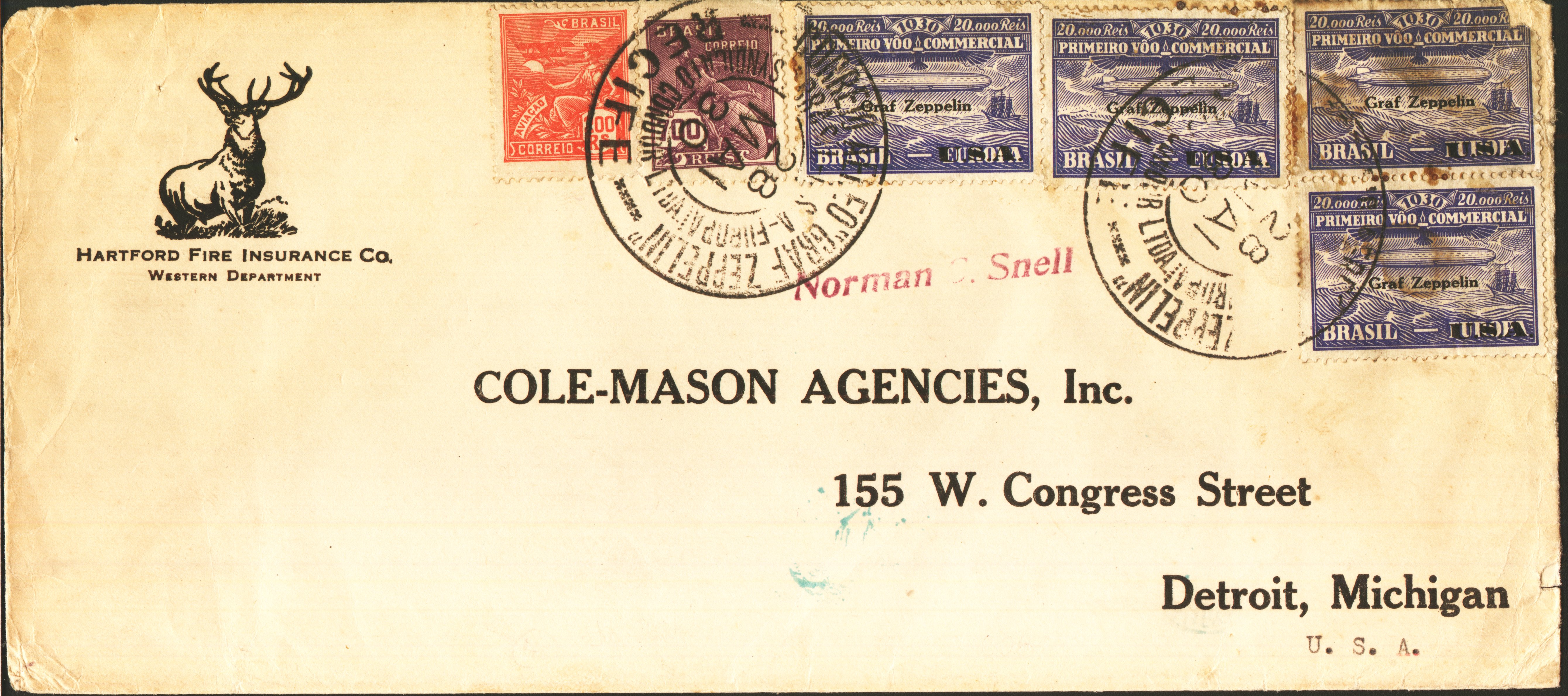

The last example is a vivid demonstration of preconceptions. For a long time, most of the literature concerning this particular flight thought that mail was restricted to single weight class mail, no overweight being allowed. My research has shown, at least what concerns mail out of Brazil, overweight letters were allowed. Since the LZ was hoping to become an important factor for the conveyance of business mail, such letters were actually encouraged. The example shown in the final Fig. 29, would be a cover whose condition would cause most judges to look askance at, but it is actually a philatelic gem. The cover is franked with 900 Reis in Brazilian postage and 80$000 in Zeppelin stamps (20$000 overprinted with “Graf Zeppelin” and “USA”).

Fig. 29: Business letter franked for 8 times the single weight of

10 grams.

Fig. 29: Business letter franked for 8 times the single weight of

10 grams.

The brown stains on the cover are not the usual “tropical” stains one sees often at auctions. Stamp gum was not very reliable in Brazil (as in most tropical countries), thus even post offices had glue pots on the counter contained an awful looking brown mess that guaranteed that the stamp wouldn't come off – a further indication of a business letter. And the Brazilian postage part, 900 Reis is also correct for a letter up to 80 grams. That puts the total postage for this letter at about $10.50, an amount that even dealers would think twice about for a philatelic cover. Even traces of impressions created in the envelope by staples indicate that important documents were being sent the fastest means available.

Thus, aerophilatelic history isn't just the cover or card front, but a piece of a whole, a historical snapshot that can even enhance the postal meaning.

References:

(*) This article was originally submitted to the American Philatelist of the APS, where some interest on this theme had been indicated. Yet when submitted, all e-mails about the articles status were left unanswered. The old saying is true, all APS members are equal, just some are more equal.

Charles A. Fricke: Travels by Sea, air & Land; American Philatelist 121(10), 960 (October 2007)

Details of the stamps and other relevant aspects of the 1930 Pan Am Zeppelin flight out of Brazil are contained in my website www.aknoth.commercial.de/Phil/